Microsoft Places

IMDF & Places – Which Way is Up? Balancing Geographic Context with User-Centric Indoor Mapping

Introduction

When you walk into your office, do you ever think about which way it’s facing (north or south) or how it’s aligned with the world outside when trying to locate a workspace?

I suspect not.

For most of us, displaying our office in relation to a geographic map might be useful when we’re trying to get there, but once inside the office, we navigate based on what we can see in front of us: staircases, lifts, any signage on the walls.

This is why, when it comes to indoor mapping for a regular office space, presenting an indoor floor plan in relation to its external geography doesn’t always make sense.

Now that Microsoft Places approaches general availability, organisations that have looked at it during the preview may have been surprised by how their office spaces are depicted using Apple’s Indoor Mapping Data Format (IMDF) standard.

This article explores how IMDF mapping conventions can impact the UX in Microsoft Places, and why you might elect to choose an alternative approach to presenting your workspace maps that prioritises a ‘Heads Up’, entrance-oriented view over strict geographic accuracy.

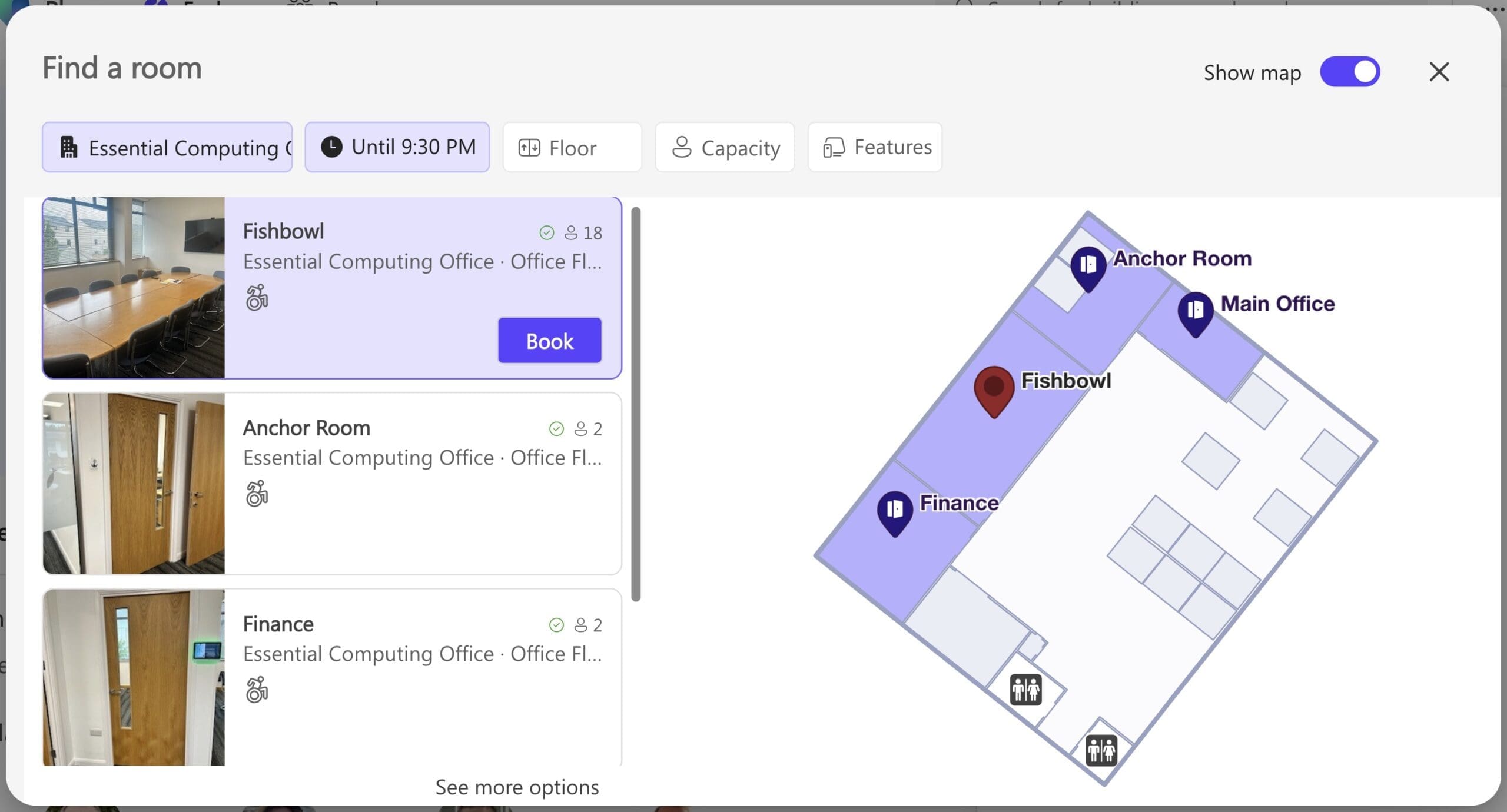

What Does an IMDF Floor Plan Look Like in Microsoft Places?

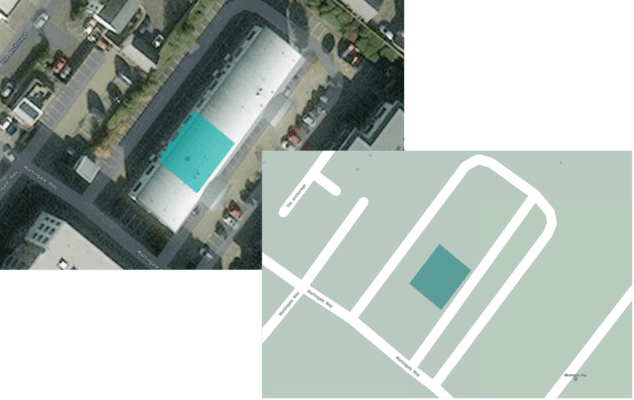

The example below shows the Essential Portishead office floor plan. As you can see, it sits at a jaunty angle!

To the casual observer, the rationale for this orientation isn’t clear.

But, when we view the underlying code for the map – say using https://geojson.tools/ – which allows the inclusion of custom layers that include a satellite view and a road map layer, you’ll see that the orientation marries up with the underlying geography.

However, this raises the question of balance: should we prioritise geographic context simply because IMDF allows it, or should we design maps that serve the end user’s experience, even if that means adjusting the orientation?

Geographic Orientation vs. User-Centric Display

While it may seem logical to present indoor maps in line with geographic orientation, this approach can often fall short of providing the best UX.

The primary goal of indoor maps, particularly in settings like office buildings, universities, and shopping centres, is to help people find their way as quickly and intuitively as possible.

In a large-scale environment like a shopping mall or airport, geographic orientation can be helpful. I get that.

But imposing geographic context onto an office map when people are pre-booking a meeting room or desk can sometimes complicate this process, especially if it positions the main entrance at the ‘top’ of the map.

Instead, a heads-up display (HUD) – where the main entrance is at the bottom of the screen – can offer a more intuitive experience.

For example, this is an alternative representation of our Portishead office.

As you can see, the entrance is at the bottom of the plan.

This approach aligns with how we naturally navigate space. If the entrance is shown at the bottom, users don’t have to mentally reorient themselves; ‘left’ on the map is ‘left’ in real life, and so on.

This setup makes navigation easier, particularly for newcomers or those unfamiliar with the building layout.

You can read more about the HUD approach in this article on best practices for floor plan creation.

Can You Change Floor Plan Orientation in Microsoft Places?

Microsoft Places uses the IMDF format for its maps – a format built on GEOJSON.

IMDF and GEOJSON comprise geo-referenced polygons. This means that each shape in your map is plotted using coordinates which are the actual latitude and longitude of their position on Earth!

You can get the latitude and longitude for your office address in Google Maps:

- Enter your address

- Click on the pin that appears

- View the URL at the top, which should include an ‘@’ followed by the latitude and longitude

For Essential’s Portishead office, this is 51.486914,-2.7633349.

IMDF mapping platforms like Pointr or MappedIn typically use your office’s latitude and longitude as a starting point to create IMDF files. They then rotate the building outline, either automatically or manually, to match its orientation on a global map. All other map elements are then aligned accordingly.

Whilst this is a great approach for a global mapping system, as we’ve already said, using it for internal office mapping does not make sense.

So yes – it is possible to change the orientation of your map in Places. This can be done simply by skipping the ‘orientation’ step and simply presenting all the office element co-ordinates in a heads up orientation.

We always give our customers the option to orient their office plans to achieve the best UX when creating IMDF files.

Conclusion

Microsoft Places and the IMDF standard are opening new doors for how we visualise and navigate indoor environments, but the ultimate focus should always be on the end user.

After all, the goal is to make sure users know exactly where they’re going when they’re inside the office.

In the future Microsoft Places map orientation is limited, but with a published API, Microsoft might enable:

- More Orientation Information: By showing an underlying map or more details as an overlay, users can better understand why their office is oriented in a certain way.

- Styling Options: The ability to customise colours, themes, icons and and other visual elements – e.g., to match your company branding or office decor. This is very limited at present – see this article on icons in Places floor plans for the latest information.

- User-driven Map Orientation: Some map viewers allow office floor plan views to be rotated by a user ‘at will’. This is not as yet supported by Places.

We will watch with interest as Places evolves.